Introduction

The Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) is one of the most frequently injured ligaments in the knee, especially among athletes participating in high-impact sports. This ligament is crucial for knee stability, particularly in activities involving cutting, pivoting, or jumping. Injuries to the ACL not only affect the immediate functionality of the knee but also pose a long-term risk of developing osteoarthritis. The incidence of ACL tears has been studied extensively, with a 21-year population-based study revealing an overall age- and sex-adjusted annual incidence of 68.6 per 100,000 person-years. This incidence is higher in males than females and shows significant variation across different age groups. Interestingly, the rate of ACL reconstruction has increased significantly over time, reflecting changing surgical indications or an increasing desire among patients to return to high levels of activity after injury (1).

ACL reconstruction surgery, which aims to restore knee stability and function, is generally successful. However, failures do occur, and understanding these failures is crucial for improving surgical outcomes. A systematic review analyzing graft failure rates in ACL reconstructions indicates that graft type does not significantly affect failure rates. This review included a wide range of graft types, such as hamstring tendon autografts, bone-patellar tendon-bone autografts, quadriceps tendon autografts, and various allografts, and found yearly graft failure rates ranging from 0.72% to 1.76%, depending on the graft type used (2).

In this context, dynamic knee arthrometers like GNRB® and DYNEELAX® are emerging as valuable tools for accurate diagnosis and monitoring of ACL injuries and reconstructions. These devices provide objective measurements of knee laxity, which is crucial for determining the severity of an ACL injury and for assessing the integrity of the ligament post-reconstruction. The precise data obtained from these arthrometers can guide surgeons in decision-making, both for initial ACL reconstruction and for considering ACL revision surgery in cases of failure. By incorporating these advanced diagnostic tools into clinical practice, it is possible to enhance the accuracy of ACL injury assessments, tailor the surgical approach to individual patient needs, and monitor post-surgical recovery more effectively, potentially reducing the likelihood of surgery failure.

This article will answer the following questions:

- What is a revision ACL reconstruction?

- Why was the first operation unsuccessful?

- How do I know if I need a second ACL Surgery?

- How can you evaluate the failure of the first surgery?

- Is a second ACL Surgery really necessary?

- What surgical techniques and graft options are available for the revision? How do they compare to what was used in my first surgery?

- What will the rehabilitation process involve after the second surgery?

- What should I realistically expect in terms of recovery and returning to normal activities or sports?

Please note that should you be interested in additional info about ACL revison surgery, we invite you to also read our other article: ACL Reinjury │ ACL Surgery Relapse: Examining the Causes, Rates, and Preventive Measures as the following article is indeed more of a guide to how is ACL revision surgery performed.

I. Background

1.1 Anatomy and Function of the ACL

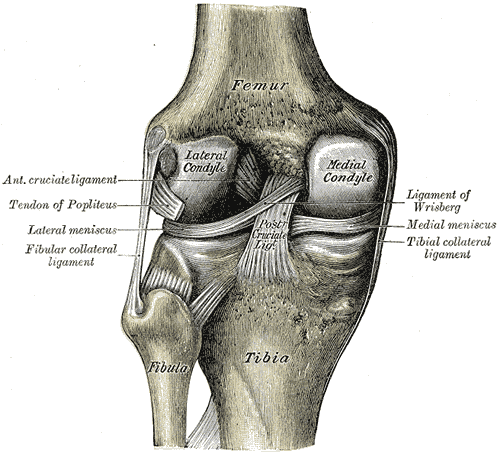

The Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) is a crucial structure in the knee joint, known for its resistance to anterior tibial translation and rotational loads. This ligament, comprising a band of dense connective tissue, extends from the femur to the tibia.

When the knee is extended, the ACL has an average length of 32 mm and a width between 7 and 12 mm. It consists of two components: the anteromedial bundle (AMB) and the posterolateral bundle (PLB), which change in length during flexion.

The ACL’s complex ultrastructural organization, which includes collagen bundles (predominantly type I) and a matrix of various proteins and glycosaminoglycans, allows it to withstand multiaxial stresses and tensile strains (3).

1.2 Standard ACL Reconstruction Techniques

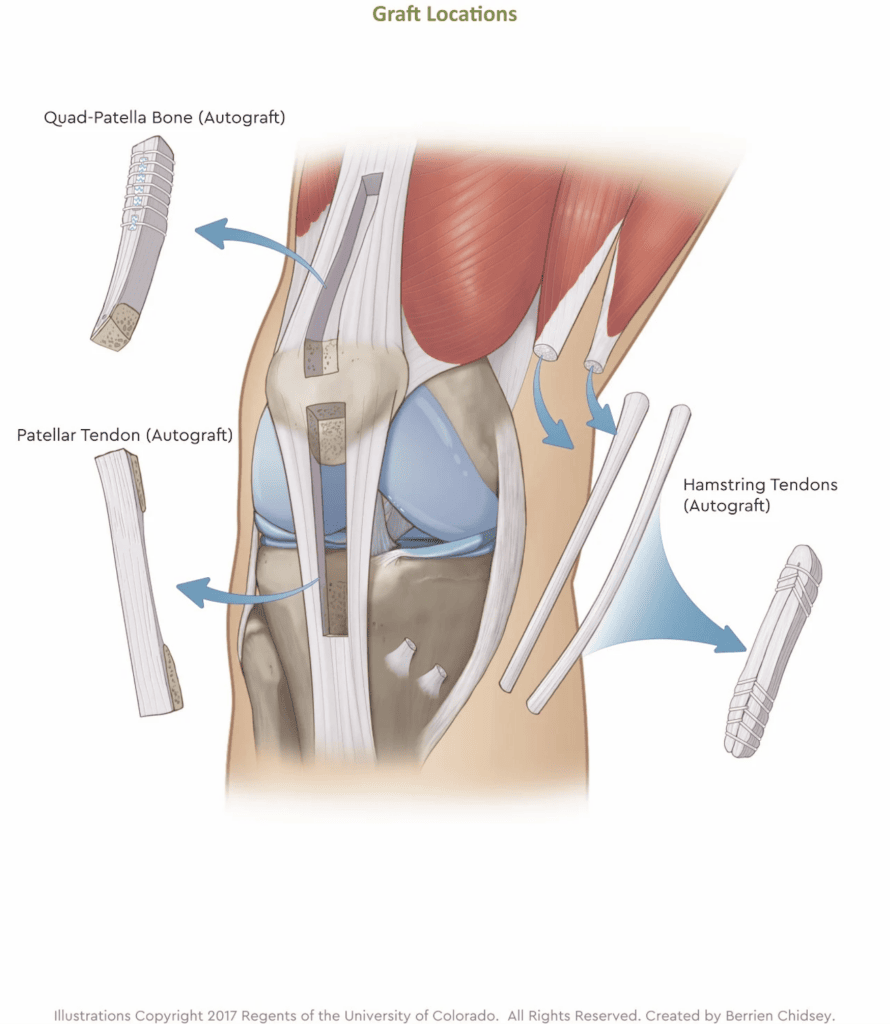

The choice of graft in ACL reconstruction—whether hamstring tendon autograft (HT), bone-patellar tendon-bone autograft (BPTB), or quadriceps tendon autograft (QT)—is significant. Each graft type has unique properties and implications for surgical outcomes.

For example, BPTB and HT autografts have traditionally been preferred for patients returning to Level 1 sports. However, the QT autograft has gained popularity due to its robust properties, such as superior collagen density and load-to-failure strength, potentially offering less donor site morbidity than BPTB and better patient-reported outcomes than HT. These factors contribute to the graft-specific surgical and rehabilitation considerations that are vital for successful ACL reconstruction (4).

1.3 Success Rates and Importance of Successful Reconstruction

The success of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction (ACLR) is vital for restoring knee stability and function, significantly impacting the patient’s quality of life and ability to return to pre-injury levels of activity. Different graft types such as hamstring tendon autograft (HT), bone-patellar tendon-bone autograft (BPTB), and quadriceps tendon autograft (QT) have specific characteristics that influence surgical outcomes. Recent literature suggests that ACLR with QT may offer less donor site morbidity than BPTB and better patient-reported outcomes than HT. Additionally, anatomic and biomechanical studies have highlighted the robust properties of the QT, suggesting its efficacy in ACLR.

Long-term outcomes following ACLR are also a crucial consideration. A study, for example, focusing on post-traumatic osteoarthritis (PTOA) risk following ACL injuries revealed that despite successful ACLR, the knee remains at risk for PTOA. The study found that initial graft tension, a factor thought to affect PTOA risk, did not significantly influence outcomes at 7 years post-surgery (5). This finding emphasizes the complexity of ACL injuries and the multifactorial nature of long-term knee health following ACLR.

Furthermore, a systematic review of ACL repair outcomes also highlighted the superiority of ACL Reconstruction over ACL repair. The review, which included studies comprising 2,401 patients, showed that overall ACL repair survivorship ranged from 60.0% to 100.0%, with high frequencies of re-rupture, revision ACL surgery, and overall re-operations associated with ACL repair, indicating the importance of choosing the right surgical strategy for ACL injuries (6).

II. Revision ACL Reconstruction

2.1 Definition and Complexity - What is a revision ACL reconstruction?

Revision Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) reconstruction is undertaken when the primary ACL repair fails. This complex procedure is more challenging than the initial surgery due to factors like scar tissue, altered knee anatomy, and compromised bone quality.

The procedure aims to correct issues that resulted from the initial surgery, such as graft failure, instability, or misalignment. Revision surgery is intricate and demands thorough preoperative planning. It requires an in-depth assessment of the prior surgery’s outcomes, including an analysis of the knee’s structural integrity, the status of the graft, and the presence of any additional knee injuries that might have been missed initially.

A key aspect of revision ACL reconstruction is understanding the reason behind the failure of the initial surgery. Traumatic ruptures are often the most cited reason for primary ACL reconstruction failure, followed by technical errors during the surgery, such as incorrect graft placement or tunnel positioning, and biological failures like poor graft healing.

The success of revision surgery hinges on accurately diagnosing these issues and developing a customized surgical plan to address them. According to recent studies, including Monllau et al. (2023) (6) and Diquattro et al. (2023) (7), a successful ACL revision surgery requires a comprehensive approach, considering a combination of surgical techniques and potentially addressing other knee injuries or structural anomalies.

2.2 Causes of Failure - Why Was the First Operation Unsuccessful?

The reasons behind the failure of the first ACL reconstruction are diverse and can be broadly categorized into biological and mechanical failures. Biological failures refer to issues with graft healing and incorporation. Mechanical failures, on the other hand, are typically related to improper graft placement, tensioning, or fixation, which can lead to instability or re-tearing of the graft.

Additional factors include overlooked knee injuries, like meniscus tears or cartilage damage, and biological failures. Comprehensive preoperative planning, including detailed medical history review, clinical examination, and advanced imaging, is essential for identifying the specific reasons for failure in each case.

The primary reason for ACL graft failure is often technical errors made during the initial surgery. The two most frequent mistakes involve incorrect placement of the ACL reconstruction graft: either too far forward on the femur, away from the back wall, or too far back on the tibial tunnel, behind the anterior horn of the lateral meniscus. These errors are consistently cited in numerous studies as the leading causes of ACL graft failures.

Additional factors contributing to ACL graft failure include the absence of a medial meniscus, which plays a crucial role in stabilizing the knee and preventing forward slippage in ACL-deficient knees. Without the medial meniscus, the ACL graft is more likely to become overstretched. Similarly, meniscal root tears and overlooked or unidentified tears in the posterolateral corner or medial collateral ligament (MCL) can also lead to the stretching of an ACL graft. Moreover, patients with an increased posterior tibial slope are more prone to having their ACL grafts overstretched.

A systematic review by Shen et al. (2021) (8) delves into various risk factors associated with ACL reconstruction failure. These include patient-related factors such as age, activity level, and body mass index (BMI). Technical aspects of the initial surgery, such as the choice of graft type and surgical technique, also play a significant role. For instance, the use of allografts has been associated with a higher failure rate compared to autografts. Resuming activities prematurely following an allograft ACL reconstruction increases the risk of failure. This heightened risk is attributed to the extended healing time required for allografts, which can be up to 50% longer than when using one’s own tissue (autograft). This delayed healing process is considered a primary factor in the 45-50% failure rate of allografts in patients under 25 years old. Furthermore, postoperative rehabilitation and patient compliance significantly impact the success of the surgery. Inadequate rehabilitation or premature return to high-impact activities can lead to graft failure.

Moreover, various studies have emphasized the importance of understanding these failure mechanisms to tailor the revision procedure effectively. For instance, Diquattro et al. (2023) highlight the significance of addressing technical errors and biological factors (7), while Monllau et al. (2023) emphasize the need for a thorough preoperative assessment to identify any concomitant injuries or anatomical issues that could impact the success of the revision surgery (6).

Adding to the diagnostic arsenal, the use of dynamic knee assessment tools such as the Dyneelax arthrometer can be invaluable. This tool offers a sophisticated analysis of both rotational and translational stability of the knee, providing a more dynamic and comprehensive assessment than traditional static tests(MRI).

By utilizing the Dyneelax arthrometer during the preoperative phase, surgeons can gain critical insights into the functional status of the knee. This can be particularly useful in detecting subtle instabilities or deficiencies that might not be apparent in standard clinical exams or MRI scans. Incorporating dynamic assessments like those provided by the Dyneelax arthrometer can lead to a more informed decision-making process, potentially identifying issues that may have contributed to the failure of the initial surgery and guiding the planning for the revision procedure. Such dynamic assessments are increasingly recognized as crucial in the preoperative evaluation, particularly for complex cases where accurate diagnosis of the knee’s functional state is essential for a successful revision ACL reconstruction.

The information provided by these dynamic assessment is also pivotal in choosing the appropriate surgical technique for the revision. Different surgical techniques may offer varying degrees of stabilization — some may be more effective in addressing translational instability, while others might better correct rotational instability. Understanding the specific type of instability present, as identified by the Dyneelax arthrometer, allows surgeons to tailor the surgical approach, including the placement of tunnels, to address the unique needs of each case. This tailored approach can be critical in ensuring the success of the revision surgery, as it directly addresses the functional deficiencies identified during the dynamic assessment.

For example, if predominant translational instability is identified, techniques like the “all-inside” method or “transtibial” technique may be preferred, as supported by a 2024 study by Ali Torkaman et al. (9) in BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders which found that combining the all-inside technique with anterolateral ligament reconstruction can improve postoperative stability, particularly in reducing translational instability.

Conversely, if rotational instability is more pronounced, the “anteromedial (AM) portal” technique might be preferred. This technique has been shown to offer better control over rotational stability, as evidenced in a 2010 study by Eduard Alentorn-Geli et al. (10) comparing it with the transtibial drilling technique, suggesting its effectiveness in addressing rotational instability.

Additionally, the “over the top” technique, as reviewed in a 2019 study by Sarraj et al. (11), indicates that this approach can yield outcomes comparable to traditional methods like all-inside, transtibial, and anteromedial portal drilling techniques in both primary and revision settings, offering a viable option in complex instability cases.

This tailored approach is vital, whether during the first surgery or during a revision procedure, as it significantly increases the overall chances of successful outcomes. By meticulously addressing the specific biomechanical issues present in each patient, these informed surgical choices can enhance recovery and long-term knee stability.

III. Identifying the Need for Revision Surgery

3.1 Recognizing Failure - How do I know if I need a second ACL surgery?

The need for revision ACL surgery often becomes apparent when the initial reconstruction fails to resolve or leads to worsening of symptoms. Key indicators include:

- Persistent Instability: A feeling of the knee ‘giving way’ during activities, indicating inadequate ligament support.

- Pain and Swelling: Recurrent pain or swelling, especially after activities, can signify a compromised ACL graft.

- Limited Range of Motion: Difficulty in fully bending or straightening the knee, which could be due to scar tissue or improper graft placement.

- Audible or Physical Signs: Popping or clicking noises in the knee, or any sensation of the knee being ‘loose’ or unstable.

Addressing “How do I know if I need a second ACL surgery?”, patients should consult their surgeon if they experience these symptoms, particularly if they persist or worsen over time. A thorough clinical examination, along with dynamic arthrometer tests or imaging tests like MRI, can confirm the diagnosis and the need for revision surgery.

Furthermore, ACL revision procedures typically necessitate a CT scan. This scan is used to assess the positioning of the tunnels created during the prior ACL reconstruction and to measure their size. This evaluation helps determine whether a bone graft is needed as an initial step. The bone graft is often required when the tunnels are too large, and it serves to fill them in, preparing for a successful first stage revision ACL reconstruction.

3.2 Special Emphasis on Arthrometers - How can you evaluate the failure of the first surgery?

In this diagnostic process, dynamic knee arthrometers like GNRB® and DYNEELAX® are excellent tools. These advanced devices offer precise measurements of knee laxity and stability, which are crucial in evaluating the integrity of the ACL graft. They provide objective data that can supplement clinical assessments and imaging findings, helping to clarify whether the initial surgery has failed. For example:

- Quantifying Translation Laxity: Arthrometers measure the degree of forward movement (anterior tibial translation), which is critical in assessing the functional competency of the ACL. Read 2023, Théo Cojean et al. (12) 2022, Miha Magdič et al. (13) 2015, Klouche et al. (14), 2017, Jenny et al. (15), 2022, Kayla Smith et al. (16) for more info.

- Quantifying Rotation Laxity: Arthrometers measure the degree of lateral & Medial Rotation which is another critical parameter: 2014, Mouton et al. (17), 2015, Mouton et al.(18), 2016, Nicolas Ruiz et al. (19), 2017, Senioris et al. (20), 2023, Théo Cojean et al.(21) for more info…

- Comparative Analysis: By comparing measurements from the injured knee with the uninjured one, or with standard values, arthrometers can help in making a more accurate diagnosis.

- Monitoring Progress: These tools can also be used in postoperative follow-ups to monitor the graft’s stability over time, aiding in rehabilitation and decision-making for potential revision surgery. Read 2016, Semay et al. (22), 2017, Nouveau et al. (23), 2023, Forelli et al.(24), 2019, Pouderoux et al.(25) for more info.

The utilization of arthrometers like GNRB® and DYNEELAX® in diagnosing ACL reconstruction failure represents the integration of advanced technology in clinical practice, enhancing the precision and reliability of assessments, which is crucial in deciding the necessity of a revision ACL surgery.

IV. Options and Decision-Making - How does revision ACL reconstruction work?

Revision ACL reconstruction is a complex and nuanced procedure, requiring careful consideration of various techniques and options based on the specific needs and history of the patient. This section outlines different strategies and approaches for revision surgery.

4.1 Special Techniques - Is a second ACL surgery really necessary?

Revision ACL reconstruction is a complex and nuanced procedure that demands a thorough evaluation of the patient’s specific knee condition and surgical history. Key to this evaluation is the use of advanced diagnostic tools like dynamic knee arthrometers, including GNRB® and DYNEELAX®, which provide objective measurements of knee laxity. These precise readings are crucial in determining the extent of instability and assessing the functional competency of the ACL graft. With this data, surgeons can make informed decisions about the necessity and type of revision surgery required, whether it involves special techniques or more traditional approaches. This section outlines the various strategies and considerations for revision ACL surgery, emphasizing how arthrometers can guide the decision towards either standard or specialized surgical techniques based on individual patient needs.

- Extra-Articular Plasty: This technique involves reinforcing the lateral aspect of the knee joint to augment the stability provided by the ACL graft. It’s beneficial in cases of residual rotational instability. A study by Ntagiopoulos and Dejour (2018) highlighted the rationale and indications for this technique in addressing combined injuries of the anterolateral aspect of the knee (26).

- Lateral Extra-articular Tenodesis (LET): LET addresses anterolateral rotational instability using a strip of the iliotibial band to create a brace effect on the outside of the knee. Rowan et al. (2019) found that LET in combination with ACL reconstruction demonstrated better patient-reported outcomes compared to ACL reconstruction alone (27). Additionally, Grassi et al. (2020) reported good mid-term outcomes and low rates of residual rotatory laxity, complications, and failures after revision ACL reconstruction combined with LET (28).

- Lemaire Technique: Similar to LET, the Lemaire technique uses a strip of the iliotibial band, but with different anchoring to provide lateral support to the knee. This technique is effective in correcting excessive anterolateral laxity. A modified Lemaire lateral extra-articular tenodesis, as an augmentation to ACL reconstruction, has been shown to reduce anterolateral rotatory laxity, especially in young patients and in revision scenarios (Jesani et al.) (29). Daniel W Green et al. (2023) evaluated the 2-year clinical outcomes of ACL reconstruction with quadriceps tendon autograft performed with a concomitant LET using a modified Lemaire technique in high-risk adolescents, finding that the rate of graft rupture was 0% and the return-to-sports rate was 100% (30). Furthermore, Andreas Flury et al. (2019) discussed the modified Lemaire procedure, indicating its efficacy in addressing anterolateral stabilization in addition to ACR reconstruction, with promising biomechanical and clinical results (31).

To sum everything up, these techniques are not about reconstructing the ACL anew but rather about supplementing the existing reconstruction to manage specific types of laxity or instability. They are valuable tools in orthopedic surgery for revision cases where complete ACL graft replacement isn’t necessary or where additional support is required to achieve optimal knee stability.

4.2 One-Stage vs. Two-Stage Surgery in ACL Revision

The choice between one-stage and two-stage surgeries depends on multiple factors, including the extent of complications from the previous surgery, the quality of the surrounding bone, and the patient’s overall health and recovery capacity. The surgeon’s expertise and the patient’s specific needs and expectations also play a critical role in determining the most appropriate approach.

In both scenarios, a thorough preoperative evaluation and planning are essential to ensure the best possible outcome. The goal is to achieve a stable and functional ACL, thereby improving the patient’s quality of life and ability to return to normal activities or sports.

4.2.1 One-Stage ACL Revision Surgery

In one-stage ACL revision surgery, the entire procedure is completed in one surgical session. This approach is generally selected under specific conditions:

- Absence of Major Complications: If the patient does not have significant complications such as major tunnel widening or infection, a one-stage surgery is often feasible.

- Sufficient Bone Quality: Adequate bone quality is essential for immediate grafting. The surgeon assesses the bone condition in the area where the graft will be placed to ensure it can support the new graft effectively.

- Advantages: The key benefit of one-stage surgery is the reduced overall recovery time and quicker return to activities, as the patient undergoes only one surgical procedure and one rehabilitation period.

4.2.2 Two-Stage ACL Revision Surgery

Two-stage surgery is considered in more complex scenarios and involves two separate surgical procedures:

First Stage – Graft Removal and Tunnel Preparation:

- Graft Removal: The initial step involves removing the failed ACL graft. This is a crucial step to clear the site for the new graft.

- Addressing Infections: If there is any infection present, it needs to be treated during this stage to prevent complications with the new graft.

- Bone Grafting for Tunnel Enlargement: Significant tunnel enlargement, a common issue in failed ACL reconstructions, is addressed by bone grafting. This step is vital to provide a stable base for the new graft.

- Healing Period: After the first stage, a period of healing is necessary. This allows the bone graft to integrate and create a solid foundation for the new ACL graft.

Second Stage – New ACL Graft Placement:

- After Healing: Once the area has healed sufficiently and the bone quality is deemed adequate, the second stage of surgery is performed.

- New Graft Placement: The new ACL graft is placed in the prepared and healed site.

- Advantages: Though this approach extends the overall treatment and recovery time, it allows for addressing complex issues that cannot be managed in a one-stage procedure. It ensures better graft stability and longevity, especially in cases with significant anatomical challenges.

4.3 Graft Options and Surgical Techniques - What surgical techniques and graft options are available for the revision?

In revision Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) surgery, the choice of graft is significantly influenced by the type used in the initial surgery. Options for grafting include autografts (tissue from the patient’s own body), allografts (donor tissue), and synthetic grafts.

Common types of autografts include the hamstring tendon, bone-patellar tendon-bone (BTPB), and quadriceps tendon, each offering unique benefits and suitability depending on the case. The decision on which type to use hinges on various factors, such as the patient’s age, activity level, the type of graft used previously, and the surgeon’s preference. Each type of graft presents its own set of advantages and considerations, making the choice critical to the surgery’s success.

Equally critical to the success of revision ACL surgery is the surgical technique employed, particularly in the creation of bone tunnels. This aspect of the procedure must be strategically tailored, taking into account not only the chosen graft but also the nuances of the initial surgery. The selection of the surgical technique is a meticulous process, involving various approaches, each with its own specific benefits and limitations. These techniques include:

- Transtibial: Accessing the knee joint through the tibia.

- Anteromedial: Targeting the anteromedial aspect of the knee.

- Outside-in: Moving from the outer knee inward.

- Over-the-top: Maneuvering the graft over the femoral condyle, suitable for complex cases.

- All-inside: Minimizing the need for extensive incisions.

- Retrodrill: Employing specialized drilling techniques.

- Transportal: Accessing the knee joint through the portal.

The decision on which surgical technique to use is dependent on several factors, including the patient’s knee anatomy, the condition of previous tunnels, and the surgeon’s expertise. However, among these various techniques for ACL revision surgery, the over-the-top (OTT) technique is gaining notable attention in ACL Revision surgery:

This method is particularly beneficial in complex revision cases where traditional tunnel-based techniques may be unsuitable due to altered anatomy or compromised bone tunnels from the initial surgery. By routing the graft over the femoral condyle, the OTT technique skillfully avoids the use of existing bone tunnels, which can be problematic in revisions. Studies have shown promising outcomes for the OTT technique. A systematic review published in 2018 found that OTT ACL reconstruction produces results comparable to anatomic ACL approaches in both primary and revision settings (11). Additionally, research focusing on revision ACL surgery using the OTT femoral route, as detailed in a 2005 study, demonstrated the technique’s effectiveness in addressing challenges associated with femoral tunnel preparation in revision surgeries (32). Furthermore, a 2017 study on OTT ACL reconstruction with a 20-year follow-up indicated good long-term results in laxity control, without significant increase in lateral knee or patellofemoral osteoarthritis, showcasing the potential longevity and effectiveness of the OTT approach (33). These findings highlight the OTT technique’s effectiveness across various scenarios, affirming its growing prominence in ACL revision surgery.

V. Pre-Surgery Considerations

Facing the prospect of a second ACL reconstruction can be challenging. Engaging in an informed dialogue with your doctor is critical for understanding and preparing for the surgery. Begin by inquiring about the failure of your initial reconstruction. Ask, “What specifically caused the first surgery to fail?” Whether it was due to the surgical technique, graft choice, post-operative rehabilitation, or an unforeseen reinjury, knowing this is crucial for avoiding similar pitfalls in the revision surgery.

Following this, delve into the evaluation methods used to diagnose the failure. Understanding the diagnostic approach, including physical examinations, imaging tests, and arthrometer assessments, is key. Next, explore the options available for the revision surgery. Ask about the surgical techniques and graft options, and how they differ from those used in your first surgery. This knowledge is vital, as different techniques and grafts can significantly affect the success of the revision surgery.

Equally important is understanding the risks and success rates associated with a second ACL reconstruction. Questions like, “What are the risks and how do the success rates compare to the first surgery?” will help set realistic expectations. Also, inquire about the long-term impact on your knee, including the potential for arthritis, knee stability, and range of motion.

Don’t hesitate to ask if non-surgical options, such as physiotherapy or lifestyle changes, could be effective, and weigh their pros and cons. A clear grasp of the rehabilitation plan post-surgery is also essential. Questions regarding the rehabilitation process, including physiotherapy, exercises, and recovery timeline, are crucial for a successful outcome.

Understanding what to realistically expect in terms of recovery and returning to normal activities or sports is also paramount. This helps in setting realistic goals and making necessary lifestyle adjustments post-surgery. Finally, inquire about your surgeon’s experience and success rates with revision ACL reconstructions. Knowing your surgeon’s track record can provide reassurance about their ability to successfully perform the surgery.

By asking these comprehensive questions, you not only gain deeper insights into the revision surgery but also empower yourself to make a more informed and confident decision. This conversation is a key step in ensuring that you are fully prepared, both mentally and physically, for the journey ahead.

V. Prevention and Recovery

Preventing a second ACL surgery is paramount for patients who have already undergone this procedure. The key lies in understanding the factors that lead to the need for a revision and actively working to mitigate them. Primarily, adherence to a structured and well-monitored rehabilitation program is crucial. The use of dynamic knee arthrometers, like GNRB® and DYNEELAX®, plays a significant role in this context. These advanced tools allow for precise measurement of knee stability and function, offering valuable feedback throughout the rehabilitation process. By closely monitoring progress, both the patient and healthcare providers can make informed decisions about the intensity and type of exercises, ensuring that the knee is neither under nor over-stressed.

Another critical aspect is the strengthening and conditioning of the muscles surrounding the knee, especially the quadriceps and hamstrings. This not only aids in stabilizing the knee but also reduces the chances of reinjury. Incorporating low-impact exercises and gradually increasing their intensity as per the guidance of physical therapists is advisable.

Regarding the recovery process from a revision ACL reconstruction, it’s essential to set realistic expectations. As outlined in the systematic review by Nelson et al. (2021), recovery from a second ACL surgery can be more challenging and prolonged than the first. Patients often experience a longer period of reduced mobility and may require more extensive physical therapy. The focus of the rehabilitation program post-revision surgery typically includes managing pain and swelling, restoring knee mobility, and gradually improving strength and flexibility.

The initial weeks post-surgery are crucial for healing, and patients are usually advised to limit weight-bearing activities. Gradually, as the knee heals, the rehabilitation program becomes more rigorous, focusing on regaining full range of motion, strength, and eventually, the ability to perform high-impact activities. Click here to read our article about the rehabilitation after ACL Reconstruction surgery.

It’s also important to note that psychological support and patience are key components of recovery. The emotional and mental impact of undergoing a second surgery and the subsequent rehabilitation journey should not be underestimated. Regular consultations with healthcare providers, setting achievable recovery goals, and having a strong support system can significantly aid in the overall recovery process.

Conclusion

In summary, understanding the intricacies of ACL reconstruction, particularly when considering a revision surgery, is crucial. The key takeaways from this discussion highlight the importance of recognizing the reasons behind the failure of the initial ACL reconstruction. Identifying these factors is the first step in preventing a repeat of the same issues. Equally important is making informed decisions about the revision surgery, which involves understanding the available surgical options, the associated risks, and the expected outcomes.

The role of dynamic knee arthrometers like GNRB® and DYNEELAX® cannot be overstated in this context. These advanced diagnostic tools have revolutionized the way knee stability and function are measured, providing invaluable data for both diagnosis and monitoring during rehabilitation. Their use enhances the accuracy of diagnostics and ensures that the rehabilitation process is tailored to the individual needs of each patient, thereby optimizing outcomes.

Looking ahead, the continuous evolution of medical technology and surgical techniques promises further improvements in the management of ACL injuries. However, the core principles of careful diagnosis, informed decision-making, and personalized rehabilitation plans remain fundamental. The journey of recovering from an ACL reconstruction, particularly a revision surgery, is as much psychological as it is physical. Therefore, comprehensive care involving psychological support and a strong support system is essential.

In conclusion, the journey through ACL reconstruction, especially when facing a revision surgery, requires a multifaceted approach. It demands a deep understanding of the causes of failure, careful consideration of surgical and non-surgical options, and the effective use of diagnostic and monitoring tools. Embracing these elements will significantly contribute to better outcomes and a more robust recovery process, ultimately enhancing the quality of life for those affected by ACL injuries.

Medical References

- Sanders, T. L., Maradit Kremers, H., Bryan, A. J., Larson, D. R., Dahm, D. L., Levy, B. A., … Krych, A. J. (2016). Incidence of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Tears and Reconstruction: A 21-Year Population-Based Study. The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 44(6), 1502-1507. DOI: 10.1177/0363546516629944

- Haybäck, G., Raas, C., & Rosenberger, R. (2022). Failure rates of common grafts used in ACL reconstructions: a systematic review of studies published in the last decade. Archives of Orthopaedic and Trauma Surgery, 142(11), 3293-3299. DOI: 10.1007/s00402-021-04147-w

- Duthon, V. B., Barea, C., Abrassart, S., Fasel, J. H., Fritschy, D., & Ménétrey, J. (2006). Anatomy of the anterior cruciate ligament. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy, 14(3), 204-213. DOI: 10.1007/s00167-005-0679-9

- Solie, B., Monson, J., & Larson, C. (2023). Graft-Specific Surgical and Rehabilitation Considerations for Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction with the Quadriceps Tendon Autograft. International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy, 18(2), 493-512. DOI: 10.26603/001c.73797

- Fleming, B. C., Fadale, P. D., Hulstyn, M. J., Shalvoy, R. M., Tung, G. A., & Badger, G. J. (2021). Long-term outcomes of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery: 2020 OREF clinical research award paper. Journal of Orthopaedic Research, 39(5), 1041-1051. DOI: 10.1002/jor.24794

- Monllau, J. C., Perelli, S., & Costa, G. G. (2023). Anterior cruciate ligament failure and management. EFORT Open Reviews, 8(5), 231-244. DOI: 10.1530/EOR-23-0037

- Diquattro, E., Jahnke, S., Traina, F., Perdisa, F., Becker, R., & Kopf, S. (2023). ACL surgery: reasons for failure and management. EFORT Open Reviews, 8(5), 319-330. DOI: 10.1530/EOR-23-0085

- Shen, X., Qin, Y., Zuo, J., Liu, T., & Xiao, J. (2021). A Systematic Review of Risk Factors for Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction Failure. International Journal of Sports Medicine, 42(8), 682-693. DOI: 10.1055/a-1393-6282

- Torkaman, A., Hosseinzadeh, M., Mohammadyahya, E., Torkaman, P., Bahaeddini, M. R., Aminian, A., & Tayyebi, H. (2024). All-inside anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with and without anterolateral ligament reconstruction: a prospective study. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 25, [Article number not provided]. DOI: 10.1186/s12891-023-07128-9.

- Alentorn-Geli, E., Samitier, G., Alvarez, P., Steinbacher, G., & Cugat, R. (2010). Anteromedial portal versus transtibial drilling techniques in ACL reconstruction: a blinded cross-sectional study at two- to five-year follow-up. International Orthopaedics, 34(5), 747-754. DOI: 10.1007/s00264-010-1000-1

- Sarraj, M., de Sa, D., Shanmugaraj, A., Musahl, V., & Lesniak, B. P. (2019). Over-the-top ACL reconstruction yields comparable outcomes to traditional ACL reconstruction in primary and revision settings: a systematic review. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy, 27(2), 427-444. DOI: 10.1007/s00167-018-5084-2

- Cojean T, Batailler C, Robert H, Cheze L. (2023). GNRB® laximeter with magnetic resonance imaging in clinical practice for complete and partial anterior cruciate ligament tears detection: A prospective diagnostic study with arthroscopic validation on 214 patients. Knee, 42, 373-381. DOI: 10.1016/j.knee.2023.03.017

- Magdić M, Gošnak Dahmane R, Vauhnik R. (2023). Intra-rater reliability of the knee arthrometer GNRB® for measuring knee anterior laxity in healthy active subjects. Journal of Orthopaedics. DOI: 10.1016/j.jor.2023.03.016

- Klouche S, Lefevre N, Cascua S, Herman S, Gerometta A, Bohu Y. (2015). Diagnostic value of the GNRB® in relation to pressure load for complete ACL tears: A prospective case-control study of 118 subjects. Orthopaedics & Traumatology: Surgery & Research, 101(3), 297–300. DOI: 10.1016/j.otsr.2015.01.008

- Jenny J-Y, Puliero B, Schockmel G, Harnoist S, Clavert P. (2017). Experimental validation of the GNRB® for measuring anterior tibial translation. Orthopaedics & Traumatology: Surgery & Research. Received: 7 October 2016, Accepted: 30 December 2016 DOI: 10.1016/j.otsr.2016.12.011

- Smith K, Miller N, Laslovich S. (2022). The Reliability of the GNRB® Knee Arthrometer in Measuring ACL Stiffness and Laxity: Implications for Clinical Use and Clinical Trial Design. Int J Sports Phys Ther, 17(6), 1016-1025. DOI: 10.26603/001c.38252

- Mouton, C., Seil, R., Meyer, T., Agostinis, H., Theisen, D. (2015). Combined anterior and rotational laxity measurements allow characterizing personal knee laxity profiles in healthy individuals. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy, 23, 3571-3577. DOI: 10.1007/s00167-014-3244-6.

- Mouton, C., Theisen, D., Meyer, T., Agostinis, H., Nührenbörger, C., Pape, D., Seil, R. (2015). Combined anterior and rotational knee laxity measurements improve the diagnosis of anterior cruciate ligament injuries. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy, 23, 2859-2867. DOI: 10.1007/s00167-015-3757-7

- Ruiz, N., Filippi, G.J., Gagnière, B., Bowen, M., Robert, H.E. (2016). The Comparative Role of the Anterior Cruciate Ligament and Anterolateral Structures in Controlling Passive Internal Rotation of the Knee: A Biomechanical Study. DOI: 10.1016/j.arthro.2016.02.017

- Senioris, A., Rousseau, T., L’Hermette, M., Gouzy, S., Duparc, F., Dujardin, F. (2017). Validity of rotational laxity coupled with anterior translation of the knee: A cadaveric study comparing radiostereometry and the Rotab®. DOI: 10.1016/j.knee.2017.01.009

- Cojean, T., Batailler, C., Robert, H., Cheze, L. (2023). Sensitivity repeatability and reproducibility study with a leg prototype of a recently developed knee arthrometer: The DYNEELAX®. Medicine in Novel Technology and Devices, 19, 100254. DOI: 10.1016/j.medntd.2023.100254

- Semay, B., Rambaud, A., Philippot, R., Edouard, P. (2016). Evolution of the anteroposterior laxity by GnRB at 6 9 and 12 months post-surgical anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. DOI: 10.1016/j.rehab.2016.07.045

- Nouveau, S., Robert, H., Viel, T. (2017). ACL Grafts Compliance During Time: Influence of Early Solicitations on the Final Stiffness of the Graft after Surgery. Journal of Orthopedic Research and Physiotherapy, 3(1), 035. DOI: 10.24966/ORP-2052/100035

- Forelli F, Le Coroller N, Gaspar M, et al. (2023). Ecological and Specific Evidence-Based Safe Return To Play After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction In Soccer Players: A New International Paradigm. IJSPT. Published online April 2, 2023. DOI: 10.26603/001c.73031

- Pouderoux, T., Muller, B., Robert, H. (2019). Joint laxity and graft compliance increase during the first year following ACL reconstruction with short hamstring tendon grafts.. DOI: 10.1007/s00167-019-05711-z

- Ntagiopoulos, P., & Dejour, D. (2018). Extra-Articular Plasty for Revision Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction. Clinics in Sports Medicine, 37(1), 115-125. DOI: 10.1016/j.csm.2017.07.009

- Rowan, F. E., Huq, S. S., & Haddad, F. S. (2019). Lateral extra-articular tenodesis with ACL reconstruction demonstrates better patient-reported outcomes compared to ACL reconstruction alone at 2 years minimum follow-up. Archives of Orthopaedic and Trauma Surgery, 139(10), 1425-1433. DOI: 10.1007/s00402-019-03218-3

- Grassi, A., Zicaro, J. P., Costa-Paz, M., Samuelsson, K., Wilson, A., Zaffagnini, S., & Condello, V. (2020). Good mid-term outcomes and low rates of residual rotatory laxity, complications and failures after revision anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction (ACL) and lateral extra-articular tenodesis (LET). Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy, 28(2), 418-431. DOI: 10.1007/s00167-019-05625-w

- Jesani, S., & Getgood, A. (2019). Modified Lemaire Lateral Extra-Articular Tenodesis Augmentation of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction. JBJS Essential Surgical Techniques, 9(4), e41.1-7. DOI: 10.2106/JBJS.ST.19.00017

- Green, D. W., Hidalgo Perea, S., Brusalis, C. M., Chipman, D. E., Asaro, L. A., & Cordasco, F. A. (2023). A Modified Lemaire Lateral Extra-articular Tenodesis in High-Risk Adolescents Undergoing Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction With Quadriceps Tendon Autograft: 2-Year Clinical Outcomes. The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 51(6), 1441-1446. DOI: 10.1177/03635465231160681

- Flury, A., Hasler, J., Imhoff, F. B., Finsterwald, M., Camenzind, R. S., Helmy, N., & Antoniadis, A. (2019). [Modified Lemaire Procedure: Indication, procedure, and clinical results]. Der Orthopäde, 48(3), 248-256. DOI: 10.1007/s00132-018-03663-9

- Yiannakopoulos, C. K., Fules, P. J., Korres, D. S., & Mowbray, M. A. S. (2005). Revision anterior cruciate ligament surgery using the over-the-top femoral route. Arthroscopy, 21(2), 243-247. DOI: 10.1016/j.arthro.2004.09.026

- Zaffagnini, S., Marcheggiani Muccioli, G. M., Grassi, A., Roberti di Sarsina, T., Raggi, F., Signorelli, C., … Marcacci, M. (2017). Over-the-top ACL Reconstruction Plus Extra-articular Lateral Tenodesis With Hamstring Tendon Grafts: Prospective Evaluation With 20-Year Minimum Follow-up. The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 45(14), 3233-3242. DOI: 10.1177/0363546517723013

- Nelson, C., Rajan, L., Day, J., Hinton, R., & Bodendorfer, B. M. (2021). Postoperative Rehabilitation of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction: A Systematic Review. Sports Medicine and Arthroscopy Review, 29(2), 63-80. DOI: 10.1097/JSA.0000000000000314